Compass Dispatch: How One Man's Terrible Business Trip Inspired the Red Cross

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Solferino

Good morning, humanitarian heroes, ethically-minded entrepreneurs, and anyone who's ever turned a spectacularly awful travel experience into something unexpectedly meaningful instead of just complaining about it on social media.

Today marks the anniversary of the Battle of Solferino, fought on June 24, 1859. It’s a date that might not ring bells unless you're particularly fond of 19th-century Italian unification wars or happen to be deeply invested in the origins of international humanitarian law. Which, frankly, you should be, because today’s newsletter is the story of how one Swiss businessman's monumentally terrible business trip led to the founding of the organization that became the International Committee of the Red Cross.

When Your Meeting Gets Cancelled by War

Henry Dunant was a well-to-do Genevan businessman with interests in what we might charitably call "questionable French colonial ventures" in North Africa. When one of his investments inevitably went sideways, because apparently people don't particularly enjoy being colonized, who knew?

Dunant decided to take his concerns directly to Napoleon III, emperor of France. This was rather like requesting a meeting with the CEO when your local branch manager has messed up your account, except the CEO happened to be one of history's most prominent examples of nephew-based nepotism.

Unfortunately for Dunant's business prospects, Napoleon III was rather occupied that summer of 1859. The emperor was busy fighting Austrians over the future of Italy, because nothing says "relaxing summer campaign" quite like attempting to redraw the map of Europe through violence.

The Worst Arrival Ever

When Dunant finally reached the village of Solferino in northern Italy on June 24, 1859, he discovered that his appointment had been rather thoroughly cancelled. The emperor had departed, but the aftermath of his armies' handiwork remained scattered across the landscape in the most horrific fashion imaginable. Thousands of soldiers lay dead, dying, or maimed in fields, on hillsides, and in ditches: the grisly remnants of one of the bloodiest battles on European soil since the original Napoleon's time.

Most people encountering such a scene might reasonably have concluded that this was an excellent time to turn around and head straight back to Geneva for a stiff drink and some serious reconsideration of their business strategies. Dunant, however, was made of different stuff.

From Banker to Battlefield Medic

Despite being traumatized by what he witnessed (and really, who wouldn't be?) Dunant didn't flee. Instead, he organized a makeshift field hospital, converted his personal carriage into an ambulance, and began helping wounded soldiers regardless of which army they'd been fighting for.

Of course, there was only so much one businessman could accomplish. He was a financier, not a physician, and the scale of suffering was overwhelming. But the experience burned itself into his memory with the sort of clarity that changes a person's entire worldview.

When Trauma Becomes Purpose

Upon returning to Geneva, Dunant found himself haunted by what he'd witnessed at Solferino. Rather than seeking therapy (not really an option in 1859) he began writing down his recollections. But Dunant didn't stop at simply processing his trauma through literature. He started asking bigger questions: What could be done to protect soldiers and civilians when warfare was becoming increasingly industrialized and horrific?

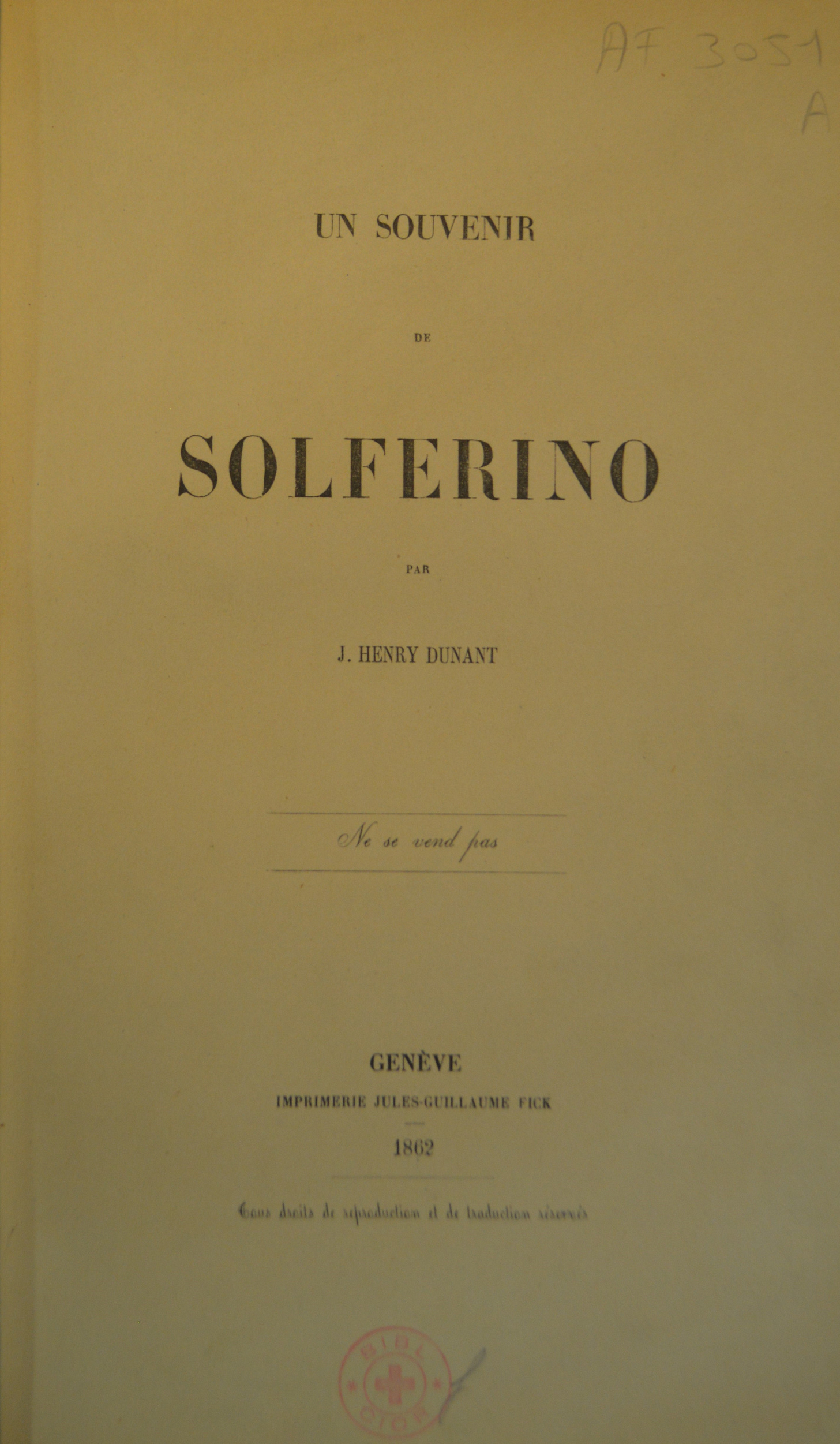

In 1862, he published "A Memory of Solferino," which he thoughtfully sent to leaders across European capitals. His publicist must have been thrilled with the marketing strategy: "Traumatic battlefield experience turned into bestselling humanitarian manifesto."

The Geneva Gang of Five

Dunant also organized a meeting with four other Geneva worthies —a general, a lawyer, and two physicians —to determine how his ideas might be transformed into action rather than merely remaining noble thoughts. The Swiss Government and this committee invited representatives from all major European powers to Geneva for a proper conference.

In 1864, the gathering produced the first Geneva Convention, establishing fundamental principles for the treatment of wounded soldiers and medical personnel during warfare. One of the most crucial innovations was the creation of a distinctive emblem to identify medical personnel on battlefields: a red cross on a white background.

This was all rather revolutionary thinking at a time when battlefield medicine typically operated on the principle of "help your own side first, if at all,” and “Is that guy on the ridge a doctor or a combatant? Tell you what, let’s just shoot him and we can sort the ID later.”

The soon-to-be famous insignia would lend its name to the organization inspired by Dunant's experience: The International Committee of the Red Cross.

Travel's Unexpected Lessons

Sometimes travel exposes us to breathtaking beauty or fascinating cultures. Other times, it confronts us with humanity's capacity for both cruelty and compassion. On June 24, 1859, Henry Dunant experienced one of the most horrific travel experiences imaginable, but rather than just filing it under "reasons never to leave Geneva again," he turned his trauma into inspiration that keeps saving millions of lives around the world.*

If you’re in Geneva and want to learn more about Henry Dunant and the history of the Red Cross, be sure to check out the ICRC Museum or join the International Geneva Tour offered by the good folks at Free Walk Geneva.**

—The By Their Own Compass Team

*Spoiler alert. In the sequel, Dunant will be forced out of Geneva by rivals in the Red Cross and the failure of his businesses.

**Shameless plug alert: Jeremiah sometimes leads walking tours for Free Walk Geneva and would love it if you joined one of them.