Compass Dispatch: Jaws at 50

How the first summer movie blockbuster changed beach travel forever

Good morning, aquaphobic adventurers, beach travelers who definitely know better but still check for approaching fins anyway, and anyone who's ever convinced themselves that the infinity saltwater pool at their hotel is probably shark-free, but you can never be entirely sure.

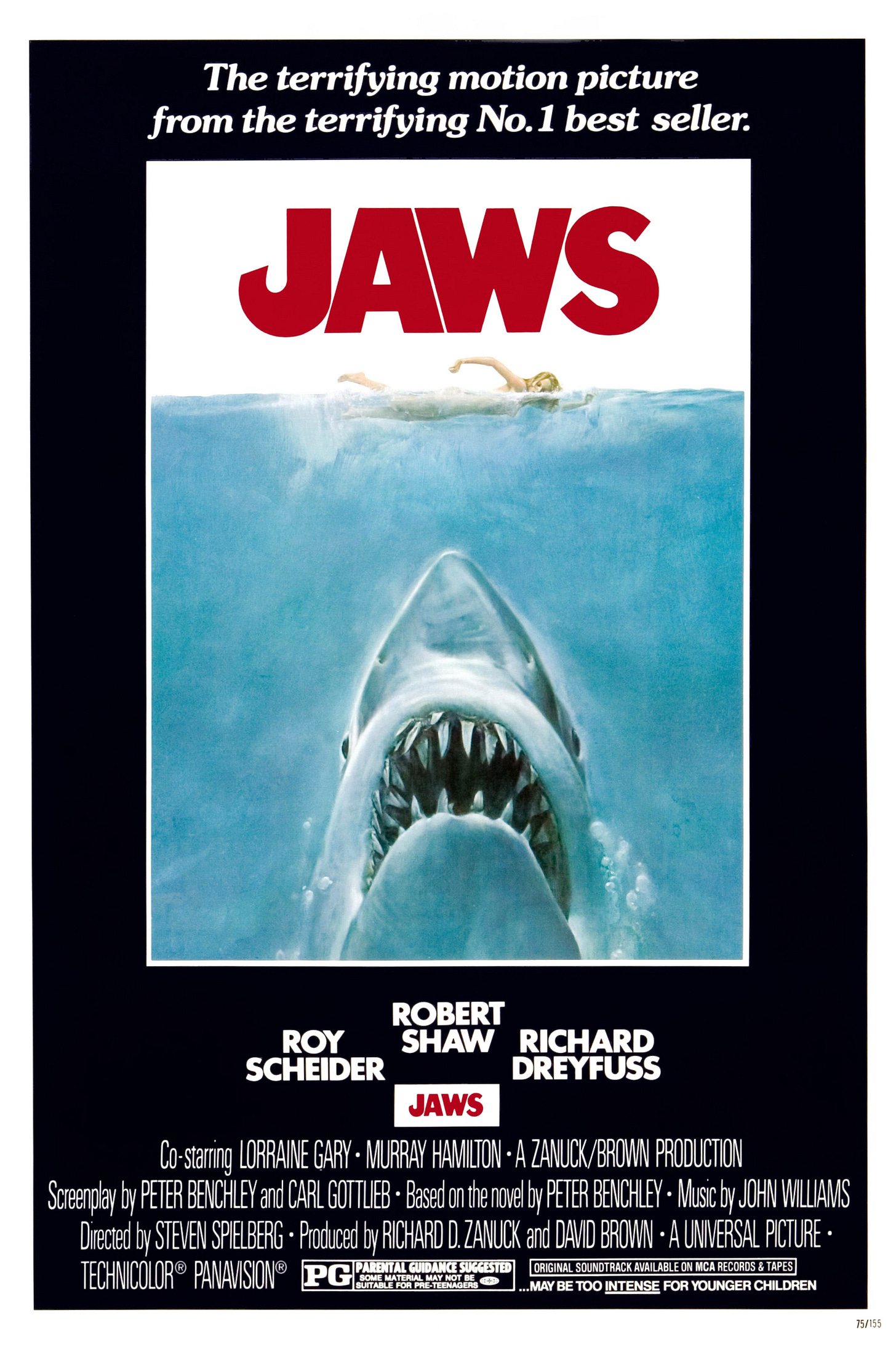

This weekend marks the 50th anniversary of Jaws, released June 20, 1975, which might seem an odd subject for a travel newsletter until you consider that perhaps no other film in history successfully convinced millions of people their summer holiday destination was actively trying to eat them.

I (Jeremiah) was a young kid when this movie came out, far too young to see it in the theater, although I did see an edited version on television that kept me out of the bathtub for at least a week. I also recall my father taking us to the local cinema a couple of years later to see the vastly inferior Jaws 2—apparently having concluded that if one traumatic shark film was good for character development, two would be positively transformative.*

So Jaws-mania was very much a part of the zeitgeist in the late 70s, a time when I was a credulous and creative child. It didn't take much to convince me that sharks were everywhere. Oceans, obviously, but also lakes, suspiciously deep mud puddles, and quite possibly under my bed, because my imagination had no respect for basic marine biology.

The Great White Effect

I was not alone. The "Jaws effect" on beach tourism was temporary (people do eventually need somewhere to go somewhere in the summer) but real and I remember swimming in New England waters, not very far from where a young Steven Spielberg had filmed Jaws, with other bathers who were no doubt also acutely aware that we might be sharing space with an oceanic predator the size of a station wagon.

That I'd never actually seen a shark was irrelevant; Spielberg had done his job rather well.

The film's genius lay in what it didn't show, a creative choice born from the refreshingly honest fact that the mechanical fish intended to be the movie’s star barely functioned. Rather like British Rail or your uncle seeking to reinvent himself in middle age as an "influencer," the shark rarely worked, and if it did, it didn’t work for long, forcing Spielberg to make a killer fish film sans a killer fish.

The result was famously more terrifying: brief glimpses of fins along the surface implying unspeakable horror lurking beneath perfectly innocent-looking waves, along with those ghastly point-of-view shots looking up at dangling human legs—defenseless limbs that bore an uncomfortable resemblance to my own pale appendages, presumably quite appetizing to an oceanic predator the size of a school bus.

The Return of the Great Whites to New England

Ironically, while my fear of sharks as a child was perhaps a bit irrational, my current concerns as an adult are more justified. New England's seal population, once nearly wiped out, has recovered remarkably and this has attracted great white sharks back to waters where I swam as an impressionable child and which I continue to enjoy as an only slightly less impressionable adult. And while the return of seals and sharks is all very good news for the environment, there have also been two recent fatal attacks in the waters around New England involving great white sharks.

Thus, I now find myself genuinely concerned about being stalked by an oceanic predator the size of a train carriage while simultaneously applauding the ecological success story that makes such encounters possible. It's rather like celebrating the return of grizzly bears to their former habitat while camping in a tent next to a cooler of sausages.**

The Real Jaws: New Jersey, 1916

While Jaws has perhaps only a tangential link to our podcast's theme of travel,*** the story does have a historical connection, being loosely based on real life events. In July 1916, something large with teeth terrorized the Jersey shore for twelve days.

Just like in the movie, local officials tried to dismiss the idea that the attacks were shark related; until fisherman Michael Schleisser killed a 7.5 foot (2.3 meter) Great White in Raritan Bay. Cutting open the shark’s stomach, Schleisser reported finding “suspicious fleshy material and bones.” Coincidentally, or not, the attacks stopped after Schleisser caught his shark.

Nevertheless, experts have since cast doubt on the culpability of a great white like the one caught in Raritan Bay in the 1916 attacks. Despite details of the incident inspiring key scenes in Jaws—some scholars now suggest it might have been a bull shark, a species known to — and I’m not sure I’m better for knowing this — occasionally swim into freshwater rivers and streams and to bite people. Several of the Jersey Shore attacks occurred at Matawan Creek, which contained brackish or even fresh water, unsuitable for a Great White, but prime habitat for bull sharks.

Fifty Years Later

Fifty years after Jaws appeared in theaters, people planning their summer vacations still wonder, "Is it safe to go in the water?" and sharks continue to hold a place in the imagination of beachgoers and travelers. We now have entire weeks devoted to shark programming and phone apps for tracking migrating great whites. Visitors to the coastal areas of New England who think watching whales is too dull can sign up for shark spotting tours. On Martha's Vineyard, the Massachusetts island playground of the Kennedy family and other elites where Jaws was filmed, gift shops now sell plush versions of the very creatures that once terrified tourists.

I'm getting ready to return to New England this summer, and yes, I'll probably go swimming at least once. Although, as always happens when toe meets water, somewhere in the back of my psyche I'll be thinking a half-century back to a movie about a fake shark that barely worked. It programmed me to spend the rest of my life wondering if every time I go near the ocean if I am being stalked by an oceanic predator the size of a Airbus380.

Because nothing says "relaxing holiday" quite like constantly scanning the horizon for fins while wondering if that dark shape in the water is seaweed or your imminent doom.

That's all from our safely terrestrial headquarters, where the most dangerous predator is the occasional aggressive squirrel.

—The By Their Own Compass Team

If this newsletter made you reconsider your beach plans, consider it a public service. Forward it to someone who thinks the ocean is "perfectly safe"—they clearly need a proper education in childhood trauma.

*There was also the follow-up decision to take me and my sister on the "Jaws Ride" at Universal Studios during a California vacation that same year. Really, it's a wonder I ever put toe-to-water again.

**Traveler's pro tip: Don't do this. Put the sausages in a bag or bear-proof canister and suspend them from a high tree branch away from your campsite. Or, alternately, put the sausages in a bag and throw them in somebody else's tent. Preferably somebody you don't like all that much and who always ruins everybody's camping trip by getting horribly drunk and vomiting in the campfire. Every. Single. Time. I mean, like twice is annoying, Bruce, but three times might be a sign that you have a real problem…

***Cut to Sarah rolling her eyes and saying “Sharks? Really, Jeremiah?”